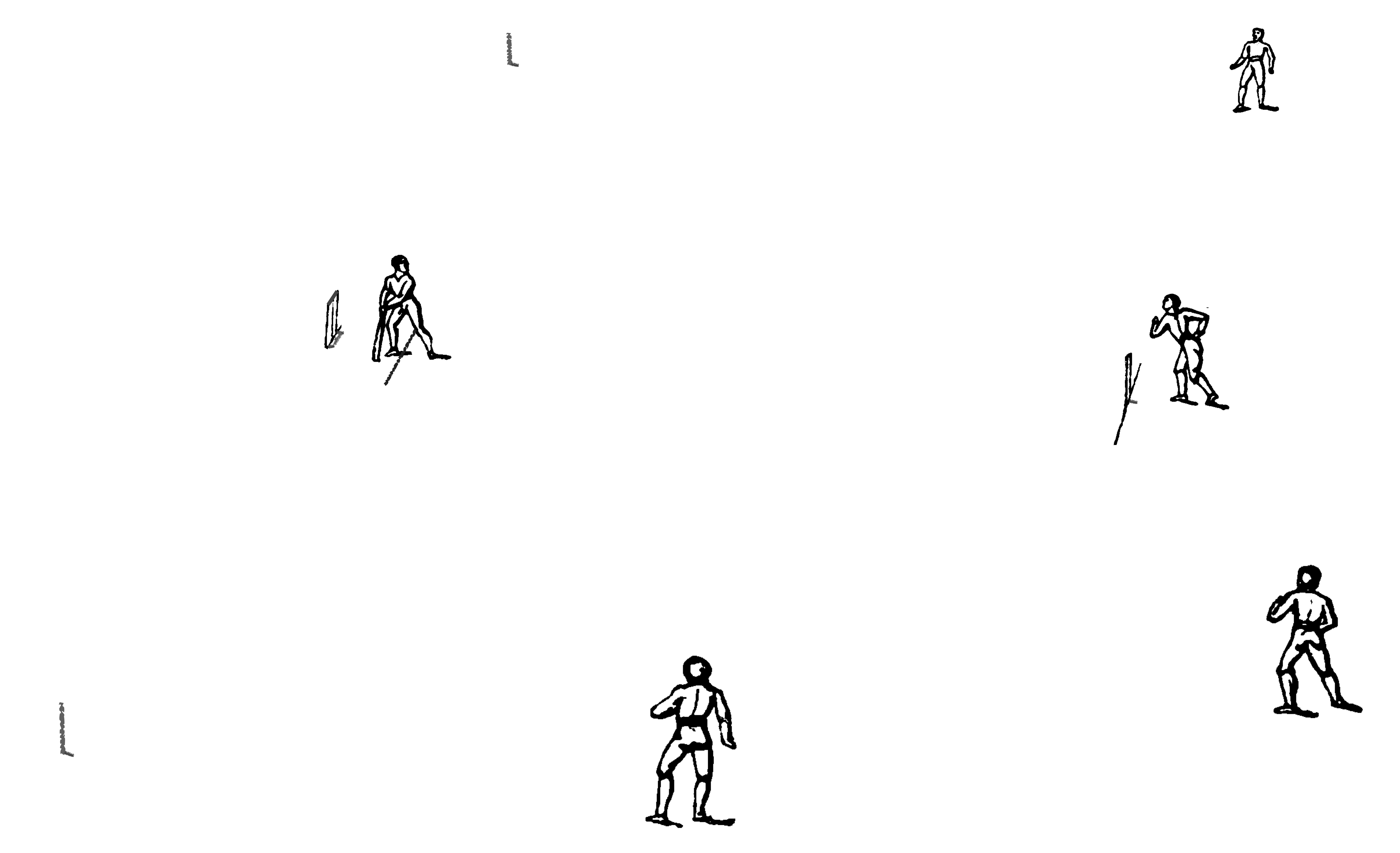

Figure 1. (After Donald Walker[6]) A representation of early 19th century single-wicket cricket, played here with four on a side. In practice, the three fielders may stand rather further from the bat. Note the stumps pitched square of the wicket on either side to mark the bounds. |

The bowler may be changed, but one player usually does the majority of the bowling. No more than one minute is allowed between deliveries[7].

Each batsman bats alone, so an innings concludes only when all batsmen have been dismissed; no-one is left not out.

At the midpoint of a run, the batsman may touch the bowling stump or bowling crease, with his bat or person, or go beyond them. The run scores only when the batsman safely reaches the popping crease.[8]

The bowling stump may be replaced by a pair of stumps with a bail across, in which case the batsman must knock off the bail when making a run. If the bail is already down, and the umpire has not replaced it, the batsman must knock a stump out of the ground[9].

The fielders may stand relatively deep, as the batsman must run two lengths of the pitch—to the bowler's end and back—to score one run.

To effect a run out, the fielding side must put down the wicket. The batsman may neither be run out at the bowler's end nor rest there.

Bounds are created by the placement of a stump, square of the wicket on either side, at 22 yards distance (see Figure 1).

There is no wicketkeeper and all fielders are stationed in front of the bounds. The bowler will usually gather returns, and must take the ball in front of the wicket to effect a run out, as once the ball passes behind the bounds it is dead.[10]

The fielding side may throw at the wicket from in front and, as the ball becomes dead upon passing behind, overthrows may not be run. A ball returned across the pitch, between the wicket and bowler's stump, also ends the play, and the batsman may not run again. In either case, the run scores, provided the batsman is not run out.

After completing one run, if the batsman wishes to make a further run, he must touch and turn at the bowler's end before the ball either crosses the pitch, or passes behind the bounds, otherwise this further run does not count.

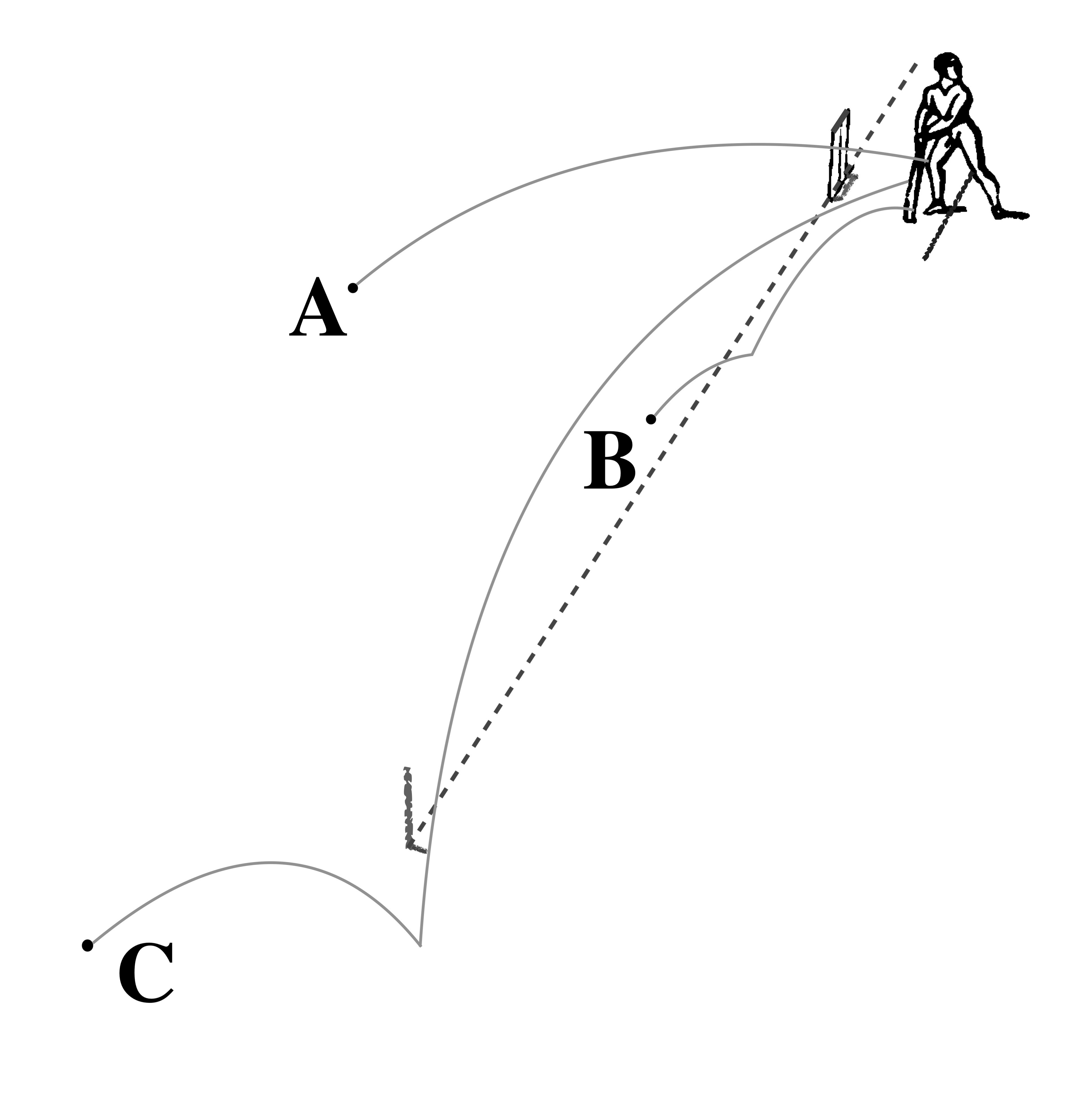

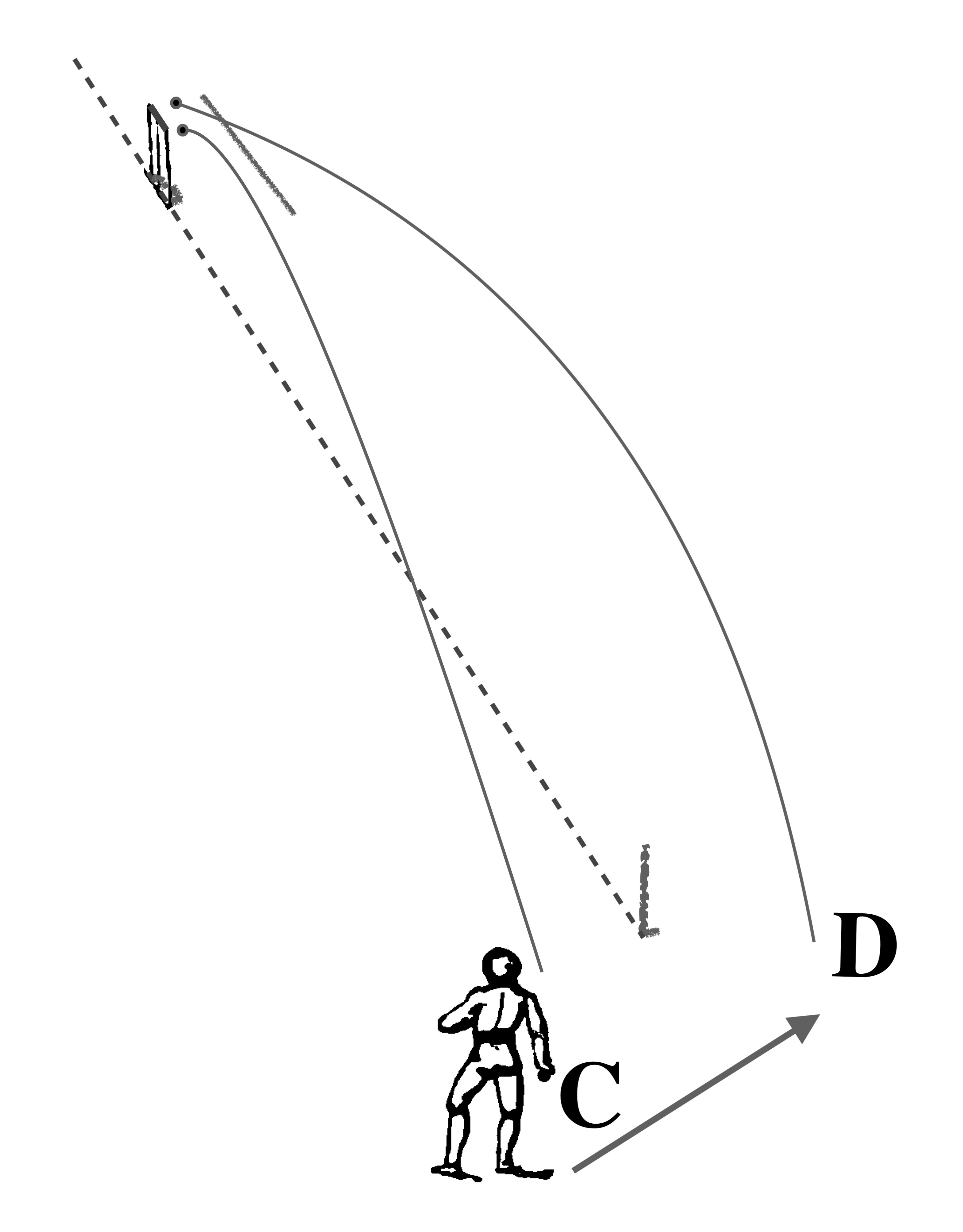

A ball which lands in front and travels outside the bounds marker remains in play, even if it then spins behind. Should this occur, the fielder must ensure that the ball is returned so as to pass in front of the bounds marker.

A ball returned from behind the bounds directly toward the rear of the wicket can do no service, and the batsman may continue to run until it is correctly returned. In such a situation, the fielders must transport the ball back around the outside of the bounds, bringing it in front of the bounds marker, before returning it to the wicket.[11]

Figure 2. Balls A and B are dead. Ball C has pitched in front and passed outside the bounds - it is in play, even though it is now behind square. If the fielder gathers the ball and returns it, behind the bounds, directly to the wicket, it is not in play and may do no service. The batsman may continue to run. If the fielder wishes to return the ball toward the wicket, he must first move to D, in front of the bounds. |

The pitch need not be at the centre of the field, but it may be necessary to employ a non-playing long-stop to gather and return balls which pass out of play behind the wicket[12], otherwise a net may be used[13].

For much of single-wicket's history, there are no perimeter boundaries and no wides, nor are there penalty runs for no balls[14]. All runs come from the bat and must be run in full, except when “Lost ball” is called at a penalty of three runs[15].

As all runs come from the bat and are run in full, and as scoring is also likely to be relatively low, keeping track of the score is straightforward for players and spectators alike. A scoreboard need only carry minimal information.

The follow on, which first appeared in the Laws of Cricket in 1835[16], had no separate provision in the single-wicket Laws. However, we do know of occasions on which sides followed on and, though only seen in one or two matches recorded by Haygarth[17], it appears frequently enough in the wider game.

A particularly high proportion of wickets are bowled out (around 80%), with caught (including caught and bowled >15%), and run out (>3%) accounting for nearly all of the remainder. A few instances of hit wicket are found, and then lbw, only occasionally, from 1825.[18]

Scorecards often feature information which would not normally be recorded at this time for double-wicket matches. For each batsman we see the numbers of balls, hits, and runs. Whilst we can be clear about what counted as runs, and might speculate as to whether or not no balls counted as balls received by the batsman, as they do in the modern game, it is difficult to say how, or indeed why, hits were counted.[19]

The bowler's end umpire must check that the bowler's back foot lands behind the bowling crease, and that the batsman touches the bowling stump when turning for a run. Appeals for lbw may also need to be answered.

The batsman's end umpire must check that the batsman's foot is grounded behind the crease when the ball is struck, adjudicate on run outs, and decide when the ball has passed behind the bounds. With no wicketkeeper to obscure the wicket, and with the batsman attempting only to hit the ball forwards, the umpire may safely stand just a few yards from the wicket, behind square on the leg side, and be well-placed to make the necessary calls.

Three 'No' calls:

'No ball' - the bowler's back foot is in front of the bowling crease[20]

'No hit' - the batsman's back foot is in front of the popping crease[21]

'No notch' - the batsman fails to touch the bowling stump or crease when running

One-on-One

In true one-on-one matches, the bowler fields alone[22], though in reports it is often not recorded whether fielders were present. In some cases we know each player to have employed one or two fielders, by agreement. Perhaps, the most famous such matches were those played between Alfred Mynn and Nicholas Wanostrocht, alias Felix, for the Championship of England, in 1846. Each had two fieldsmen[23].

All Round the Wicket (All Hits)

When the game is played without bounds, play is all round the wicket. The batsman may now be caught behind or stumped, but may profit from strokes behind the wicket, byes and overthrows. A wicketkeeper and other fielders may be stationed behind the wicket. Matches may be played all round the wicket by agreement, but the Laws specify this for matches between sides of five or six players[24].

Odds Matches

When matches are played between sides of unequal numbers, bounds are usually applied equally. If, for example, three top-class players play against eight club players, both sides play in front of the wicket only[25].

Every Man for Himself (King of the Castle)

Informal games may be played without division into teams. All players field, and batting takes place either in a pre-arranged order, or the player who dismisses the batsman takes up the bat. This is where most of us started, with a bat, a ball, and a wicket.

Haygarth A, Cricket Scores and Biographies of Celebrated Cricketers

Rait Kerr RS, 1950, The Laws of Cricket, Their History and Growth, Longmans, Green and Co.

Crawley, 1866, Cricket: Its Theory and Practice, pub. W&R Chambers

Ashley-Cooper FS, 1900 At the Sign of the Wicket, Cricket

Morrah P, 1963, Alfred Mynn and the cricketers of his time, Constable

1 ^ The 1774 Laws of Cricket contain just one line referring specifically to single-wicket: “In single-wicket matches, if the striker moves out of his ground to strike at the ball, he shall be allowed no notch for such a stroke.” This one line would remain the only direct mention of single-wicket, in editions of the Laws deemed reliable by Rait Kerr, until 1823, when expanded Laws appeared. In time, these would settle into a ten-point format, and undergo only minor modification over more than a century.

2 ^ Only from 1884, it seems, was it felt necessary to specify in the Laws that the over did not apply: “There shall be no restriction as to the ball being bowled in overs…”

3 ^ THE LAWS OF CRICKET Revised by the Marylebone Club in the Year 1823, Printed by Carpenter and Son, Engravers and Printers, 16 Aldgate High-Street.

Broadsheet in Sloane-Stanley Collection, copy by RS Rait Kerr, Lord’s Library. See also, Haygarth Vol. II, p135, (Haygarth lists as 1831, but Rait Kerr identifies as 1830) single-wicket Laws as 1823 edition.

4 ^ See Note 1, above.

5 ^ The Laws of Cricket, any reliable edition, 1823-1945

6 ^ Donald Walker, 1837, Games and Sports, London, Pub. Thomas Hurst

7 ^ See Note 5, above.

8 ^ ibid.

9 ^ William Lambert, 1816, Instructions and Rules for Playing the Noble Game of Cricket. See: Haygarth, Vol. I, p387.

10 ^ ibid.

11 ^ See Note 9, above.

12 ^ Haygarh, Vol.II, p464, notes of single-wicket game, “It is presumed this match was privately played at one corner of the ground.”

13 ^ Crawley, p20 “The long-stopping or wicket-keeping net is very useful in a field of few players, as it saves a good deal of running after the ball behind the wicket. A net 6 yards long by 2 yards wide, with poles complete, costs about a guinea.”

14 ^ Rait Kerr. Boundaries first mentioned in 1884 Code (p81); wides Law appears for the first time by 1811, scored as byes (p74), however byes did not score in single-wicket matches played before the wicket; allowance for wide entered as such from 1828 (p77); no ball penalty run introduced in 1829 (p77).

Penalties for wides and no balls at single-wicket would have seemed heavy (as matches were low scoring) and appear not to have been immediately adopted.

15 ^ See Note 5, above.

16 ^ Rait Kerr, p78

17 ^ Haygarth, Vol. II, p559, Sept. 23 and 24, 1840, Three of Chaddesden and Burton-on Trent v. Two of Nottingham, at Leicester, “The two of Nottingham followed their innings, it being (it is believed) the only record of a side following their innings at single wicket (except Osbaldeston v. Two of Nottingham, August 21, 1815); nor does the Law state a side is to follow its innings, except at double wicket.”

18 ^ In single-wicket matches listed by Haygarth in Scores and Biographies Vols I & II, 1360 dismissals are recored. Amongst these, 928 (79.73%) are bowled, 147 (12.63%) are caught, 31 (2.66%) are caught and bowled, and 43 (3.69%) are run out. In double wicket matches around this time, the proportion bowled is 50-60%.

19 ^ Haygarth, all volumes, e.g. A Single Wicket Match Lord’s, July, 1800. Vol.I, p273

20 ^ The front foot no ball Law was adopted in 1963.

21 ^ It is presumed that the batsman could be out from a no hit, otherwise he might benefit from his own infraction, but the parallel with the no ball Law is striking. Rait Kerr (p68) suggests, “it would seem that the ball was regarded as dead [on the call of no ball] so that the striker could not score off it.” Only from around 1811 do the Laws state that the batsman may play a no ball and profit.

22 ^ e.g. Haygarth, Vol.II, p29, August 5, 1827, at Lord’s, JH Dark v. J Cobbett

23 ^ Morrah, Chapter V, pp148-162

24 ^ Ashley-Cooper, p51, notes a 3-a-side match in 1747, in which, ‘All hits behind the wicket counted, and in this respect “differed from all other single matches.”’ He also lists 5-a-side matches, in 1748 and 1749 in which “Bye-balls and overthrows counted.” Yet after the publication of Laws requiring 5- and 6-a-side matches be played all round the wicket, Haygarth records only two 5-a-side matches; 1840, Haygarth Vol.II, p596 1848, Haygarth Vol.III, p580; he gives no account of two sides playing with six.

25 ^ e.g. When EM Grace and J Jackson played against Eleven of Castlemaine, in 1864 (Haygarth Vol.VIII, p255) bounds were in use when the Castlemaine XI fielded.